To Wash Hands of Palm Oil Unilever Embraces Algae

Consumer-Goods Maker Invests in California's Solazyme to Avoid Environmental Concerns Associated with Palm Oil

The Wall Street Journal

By Paul Sonne

September 7, 2010

LONDON—As food and consumer-goods companies face problems obtaining the key ingredient palm oil without damaging the environment, Unilever is betting on a promising low-life alternative: algae.

London-based Unilever, which relies on palm oil to make Dove soap, Vaseline lotion and Magnum ice cream, is set to announce Wednesday that it has made a multimillion-dollar investment in Solazyme Inc., a South San Francisco, Calif., company that harvests algal oil, a liquid that can replace palm oil in foods, soaps and lotions and serve as biodiesel fuel to power airplanes.

Unilever's investment comes as big food companies are under pressure from environmentalists to curb the use of palm oil, the harvesting of which has contributed to deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia, damaging orangutan habitats.

Using algal oil in lotions or foods could help food companies pump up their green credentials, while reducing the companies' exposure to volatile markets for commodities such as palm oil, soybean oil and almond oil.

Still, algal oil likely won't replace natural oils anytime soon. The primary question is whether algal oil can be produced in sufficient quantity at a competitive cost to naturally harvested oils.

And algal-oil products will have to go through rounds of testing with consumers before consumer-goods companies put the products on shelves.

Unilever has spent months testing Solazyme's algal oil in soaps and lotions but says it is still three to seven years from rolling out algal oil as an ingredient, as the company works out supply-chain development and continues product testing.

But the consumer-goods giant is confident that Solazyme can produce the oil on the right scale to become a viable supplier. The companies declined to be specific about the amount of Unilever's investment, which is part of a $60 million round of funding from various sources.

"This isn't just a niche application," says Phil Giesler, director of innovation for a Unilever unit that invests in new technologies. "This is something which we believe has tremendous capability."

Solazyme is among several biotechnology companies using algae to produce oils. Founded in 2003, the company takes cheap, readily available plant-matter such as prairie grass, sugar cane and corn husks and feeds it in big tanks to single-cell organisms, or microalgae, that have a natural capacity to make oil. Other algae companies use photosynthesis.

Unilever's investment in Solazyme is meant in part to help avoid incidents like one in 2008, when activists dressed as orangutans scaled Unilever's headquarters on London's Thames Embankment to call attention to rain-forest destruction.

Nestlé SA, which uses palm oil in Kit Kat candy bars, has faced similar protests. This March the British tabloid the Sun ran the headline "Kit Katastrophe" alongside a photo of two primates, after the environmental group Greenpeace criticized Indonesia's PT Sinar Mas Agro Resources & Technology, a major supplier of palm oil to Nestlé, Unilever and Kraft Foods Inc., among others.

Nestlé, Unilever and Kraft since have dropped PT Smart as a supplier, though the Indonesian company has denied Greenpeace's allegations. Nestlé this year announced a "zero deforestation" policy, with guidelines to ensure its products don't cause deforestation. Nestlé declines to comment on whether it is testing algal oil.

Kraft says it is looking at alternatives to palm oil but that it is too early to talk about them specifically.

Consumer-products giant Procter & Gamble Co. says that while it is committed to sustainable resources, it isn't pursuing algal oil at this point.

The world's biggest buyer of palm oil, Unilever sops up 3% to 4% of the global market, according to the company. Unilever and Nestlé have committed to sourcing all their palm oil from certified sustainable sources by 2015.

Paul Polman, who became Unilever's chief executive early last year, has pushed green initiatives, aiming to double sales while decreasing the company's environmental impact, in part by harnessing new technologies in areas such as packaging and refrigeration. The Solazyme investment is a sign that algal oil—recently approved as a food ingredient in the EU—could be part of the equation too.

"The potential is enormous, but really this has been almost completely ignored until the last two or three years," says Alison Smith, professor of plant sciences at the U.K.'s University of Cambridge.

Algal oil's significance for consumer goods has been overshadowed by its use as a potential alternative fuel source. Oil company Chevron Corp. has invested in Solazyme. And Exxon Mobil Corp. last year announced a $600 million algae program with Synthetic Genomics Inc., led by genomics scientist J. Craig Venter. Sapphire Energy Inc., a key algae player focused on "green crude production," is backed by Bill Gates. Synthetic is also exploring the use of algal oil for food, while Sapphire says it is focusing on using algae for transportation fuels.

Though Solazyme has been providing algae-derived jet fuel to the U.S. Navy for testing and certification, the company is equally interested in things such as ice cream and lotion.

"We've made all kinds of food products," says co-founder Jonathan Wolfson, Solazyme's CEO. "We've used the oil for frying. We've made mayonnaises, ice creams. And they work, taste good and are functional."

He said the company has also made face creams, which have proven popular in trials. Now, Solazyme is focusing on building a commercial facility to prepare for high-volume output.

Solazyme can engineer "oil profiles," devising replacements for different types of oil, by optimizing algae strains through genetic modification or conventional breeding techniques.

Mr. Wolfson says the oils tested in consumer products haven't been genetically modified, though he hopes consumer fears around genetic modification will abate. "In the meantime, we're going to go where the market tells us we have to go," he says. "We'll use natural strains where the market calls for it."

Paul Sonne at paul.sonne@wsj.com

Reuters

Reuters

Unilever came under fire in 2008 as Greenpeace activists, above, protested use of palm oil from rainforests.

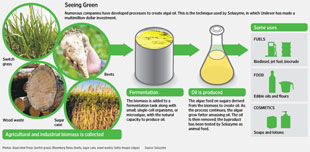

Seeing Green

Associated Press (switch grass); Bloomberg (beets, sugar cane, wood waste); Getty Images (algae)

Associated Press (switch grass); Bloomberg (beets, sugar cane, wood waste); Getty Images (algae)

Numerous companies have developed processes to create algal oil. This is the technique used by Solazyme, in which Unilever has made a multimillion-dollar investment. View full size.

In the Lab

The Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Texas has seen a spike in interest in its specimens, as inventors try to engineer oil-producing algae. Russell Gold reports from Texas.

Solazyme

Solazyme

Unilever has invested in exploring algal oil as a replacement for the palm oil in Dove soap and other products